In Education in Italy part one I describe the decline of the Italian Education system since the beginning of the new century and the birth of the scuola/azienda, of the student/customer and of the consumers’ school, with its parallel downgrading of the role of teachers and students. In this post I’ll try to present the two topical reforms of this period, Berlusconi’s 2010 Riforma Gelmini and the newly approved La Buona Scuola by Renzi’s cabinet.

- Is there really nothing buono in both of them?

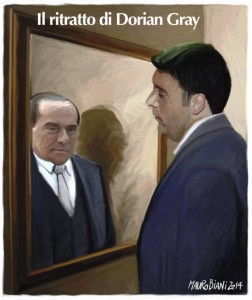

- Are Berlusconi and Renzi’s reforms the first and the second parts of the same foul play?

- After Berlusconi’s creation of the school/enterprise, of the headteacher/manager and of the student/customer, what is Renzi’s teacher/consumer?

- Are pedagogists and technology burning teachers out definitively?

- Are there any chances left to teach something worth knowing?

Berlusconi’s bosoms, football and money: Culture and Education as il Cavaliere’s worst enemies

Thanks to radio and television, he [tomorrow’s dictator] is in the happy position of being able to communicate even with unschooled adults and not yet literate children… to condition a million or ten million children, who will grow up into adults trained to buy your product… Dictators and the would-be dictators have been thinking about this sort of thing for years… millions, tens of millions, hundreds of millions of children are in process of growing up to buy the local despot’s ideological product and… to respond with appropriate behavior to the trigger words implanted in those young minds by the despot’s propagandists wrote Aldous Huxley in his 1958 essay Brave New World Revisited. When Berlusconi came to power in 1994, the road to the downgrading of public education was already wide open. A populist ruler like il Cavaliere, who used his private media empire like a real weapon of mass deception to brainwash the viewers/voters through his commercial and political propaganda – the two actually being the sides of the same medal – considered culture and education his worst enemies, it is plain to see.

But more than just painfully partial towards its boss, Mediaset television has achieved something even more disguised. It has seduced a society to the extent that politics and ideas don’t seem to exist. Italy’ s noble visual culture has been reduced to endless erotica, and the small screen is now a cheaper, bittersweet version of La Dolce Vita: a world obsessed with celebrity and sexuality, to the exclusion of all moral values (Fellini, not surprisingly, for years objected to his film being shown on television). In many ways, the real problem with Mediaset isn’t that it is political in the purest sense; it’s that it’s not political at all. The only thing on offer are bosoms, football and money

writes T. Jones in his 2003 book The Dark Side of Italy, probably the best book on my country of the new century.

Bosoms, football and money are indeed what the ‘immoral majority’ of the Italians want. The gut feelings they have, la pancia as we call it, the ethic values upon which these people’s lifestyle rests, are what Berlusconi’s networks sanctify. Easy sex, sport obsession, appearance, shortcuts to success, selfish attitude, menefreghismo (‘I don’t carism’, ‘each-to-his-own mentality’), trasfomismo, the breaking of any rules for personal purposes and, above all, obsession for wealth, a mania that matches the British care for class: these moral disvalues have been implanted into the Italian psyche like a pandemic with no antidote. Not just the manipulated news, but all Mediaset TV programs subliminally carry on these values: talk-shows, fiction (in the Italian meaning of TV dramas), entertainment, sport, reality shows, quizzes, sitcoms, American B-movies and so on.

The Riforma Gelmini

Berlusconi set out on the downgrading road quite early in his rule. He invented the slogan ‘La scuola delle tre I: Inglese Internet Impresa’, demagogic in itself and false in reality – I can affirm it without any doubt as a teacher of English – to promote his first reform in 2003, the Riforma Moratti, which continued the development of the ideology of the scuola-azienda established by the Riforma Berlinguer in 2000. But the biggest blow to the public education system came in 2010 with the Riforma Gelmini, a (counter-) reform which had no background ideas and did not spring from any didactic or pedagogic project and whose aim was to brutally cut funding to State schools, reduce the school timetable, lower the level of education given to its ‘customers’ and raise the amount of money given by the State, illegally, to privately run schools: it was the final triumph of the scuola-azienda and the final degradation of teachers and professors. All this was called a ‘rationalization’ of the system since the scuola elementare, the scuola media inferiore and superiore and university were reshaped. The Italian scuola elementare (duration 5 years, for 6 to 11 year old pupils) is the primary/elementary school, the scuola media inferiore (3 years, 11 – 13) is the secondary/junior high school and the scuola media superiore (5 years, 14 – 19) is the secondary/high school. The scuola media superiore was divided in seven different indirizzi, both tecnici (comprehensive) and licei (grammar schools).

Differently from the UK, in Italy State schools are called scuole pubbliche while privately owned schools are called scuole private. The State has always given money to private schools illegally because it is forbidden by our Constitution, which says that private schools can be established but senza oneri per lo Stato – ‘without expenses for the State’. The amount of the taxpayers’ money given to scuole private has increased constantly since the Berlinguer Reform, regardless of the government in charge, while the money given to public (State) education has taken the opposite direction since those days even if, as we say, there are many public schools without toilet paper. And this fact has political reasons and it is a reflection of the all-Italian corruptive system turning ‘legal’. Again differently from the UK, Italian scuole private are either Catholic schools or diplomifici, sometimes both of them. Diplomificio is, literally, a place where diplomas are made industrially, like a panificio (bakery) is the place where pane (bread) is produced. Diplomificio is a very derogatory neologism since it refers to a privately owned school which gives a final diploma to any student, regardless of his capacities and attitude to study, just because he has paid a high enrollment fee. It is the bribe system so dear to our country that has been ‘legalized’. The naughty students of rich families, who fail in public schools, usually at scuola media superiore where actually merit is evaluated for the first time, go there to pasture like sheep on a slope waiting for the final ‘piece of paper’. On the other hand, the Catholic Church is a very powerful lobby that can manipulate most of the politics. Catholic schools are very ideologically oriented and rich families per bene send their scions to that protected environment of peers, less detectable diplomifici which, anyway, usually guarantee success. Of course, prestigious scuole private exist in Italy, but there are just a few; generally speaking, the State school guarantees – or used to guarantee – a much higher standard of education.

For any man of culture to accept the standard of his age is a form of the grossest immorality: a speech against the subtle ways to violate the Constitution

I clearly remember the freezing 2010 January morning in which I delivered my speech on the Reform in the wonderful Piazza Maggiore in Bologna. The fog embraced the square like a cloak and all around the surrounding hills, white with snow, peered tremulously through like frozen mystical spectators. It was a suspended, unreal atmosphere that again I took as an omen to the events. I started my speech quoting one of O. Wilde’s aphorisms that seems to be extremely contemporary: Modern morality consists in accepting the standard of one’s age. I consider that for any man of culture to accept the standard of his age is a form of the grossest immorality. What I meant was that our present public morality forced us to accept the violence against the Constitution that had been going on – and does go on now under Renzi’s rule – for some time in different ways. I said there were evident ways to do it, like the proposed rewriting of parts of our Chart in order to shrink democracy by getting rid of the weights and counterweights it guarantees, like the infamous Berlusconi’s laws ad personam or like the media delegitimization of the Magistracy. But there were also subtler ways to violate the Constitution that states, in the first part dedicated to general principles, that the Magistracy and Education are two main pillars of our Republic. This subtler way is not allowing the professionals working for the State to do their jobs because of the working conditions in which they are forced to operate. That was what was happening in my field and I explained it with a paradigmatic example, of which I was the protagonist, of the degeneration of Education due to the Riforma Gelmini. When I obtained my position as permanent teacher of English in 1991, I was teaching in a State liceo linguistico in which I had 6/8 classes (teaching hours) a week for each class (units into which students are divided) with half of the students, a procedure called maxisperimentazione linguistica established to improve the teaching of English in a country in which the knowledge of foreign languages has always been very poor. In the course of time, due to the decline of Education, the teaching hours per week were progressively reduced and from the following year I said I would be forced to have 3 teaching hours a week per class in the final trienno, thanks to the effect of the Riforma Gelmini (which is what I actually have now, in 2015, since I still teach in the same type of school) but I would have to keep the same curriculum. Consequently, the number of my classes (units of students) and of my students would almost double, since our teaching time is 18 hours per week (today in fact I have 5 classes, units of students, instead of 3). According to the Minister, the halving of the teaching hours per class seemed to be the best way to teach the main subject in a school of languages. Can one think of a different word than pantomime?

The algid Berlusconian curtain: teaching in videocratic times

To make the heavy burden today’s teachers carry on their shoulders even harder, Berlusconi Age’s brainwashing and the foolish development of communication technology has made teaching a mission almost impossible, as I write in an article titled l’algida cortina berlusconiana: insegnare in tempi videocratici published in 2010. The media mainstream Jones refers to in the passage I cite earlier in this post not only indoctrinates the young ideologically, but has made it impossible for today’s student to dedicate himself to study like generations of pupils did until yesterday. The addiction they have to smartphones and similar devices has reduced to a maximum of 10 minutes the time in which they are able to concentrate on a text, at home or at school. And they don’t see the reason why they should do it since they are surrounded by a ‘videocracy’ that tells them that appearing and appearance are the important things and, consequentially, a reality show is much more important than years of study. Not to mention the fact that you can be a starlet or a Member of Parliament – the two careers being equivalent – if you are a good-looking unscrupulous guy or, better, a beautiful girl who get to know the right papi, skipping all the traditional steps and regardless of merit.

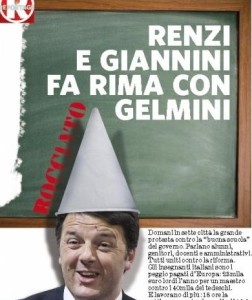

Matteo Renzi, a Demolition Man plus royaliste que le roi

Matteo Renzi got to the throne in 2014 as Demolition Man, il rottamatore, who was supposed to break with the corrupt Italian politics and start a new age of modern progressive reforms. Actually, he was just the next uomo forte, the absolute leader the Italians have loved so much since the Mussolini ventennio. Despite his speeches – Renzi has learnt Berlusconi’s media management really well – after one and a half years no real privilege has been attacked and the continuity of Italian bad politics is a fact. Paradoxically, Renzi has continued Berlusconi’s conservative politics disguising it as progressive since he is the leader of the Democratic Party, the party that springs from the old Communist Party. Today the Partito Democratico is a degraded new version of the mafia-linked corrupt centrist Christian Democracy Party who dominated Italian politics in the days of the First Republic. Renzi is Berlusconi’s legitimate heir, the son he never had, and this fact is allowing Renzi’s government to pass most of Berlusconi’s reactionary reforms il Cavaliere was never able to set up. Renzi is obviously more presentable as a person and as a leader than the truculent Cavaliere, but his clean-cut-kid face is politically dangerous and a further proof that ours is the age of ‘unique thought’.

Renzi’s Jobs Act, for example, follows Fiat/Chrysler CEO Marchionne’s logic in job contracts: it weakens the role of unions, put an end to nationwide contracts but gives bonuses to the workers who behave properly, allows the master to fire his employees without a right reason, so that every worker is limited in his freedom. It is all very Thatcheresque, I daresay, or maybe even XIX centurish.

The genesis of La Buona Scuola: social blackmail

Like every uomo forte who came to stay, Renzi put his own Reform of Education at the top of his agenda, together with the making of a new electoral law and the changing of parts of the Constitution, a very slippery ground that had alarmed many authoritative constitutionalists, as I have suggested before. In his inaugural speech in February 2014, Renzi recalled his old elementary school maestra as a model, declaring that teachers must get back to centre stage and regain the social position they deserve. This would be the aim of his reform, he said. It all sounded very suspicious to a listener like me because this is basically what every past PM had said before his disastrous reform, the same kind of demagogic propaganda. The fact that Renzi’s wife was a temporary teacher in a private school was not a good omen; on the contrary, it increased suspicions. Some months later the first draft of the reform, paradoxically called La Buona Scuola, was presented and it immediately looked worse than I expected. It instantaneously raised the hostility of all the school unions, of almost all of the teachers and of that small portion of decent politics that survives in Italy. But Demolition Man never listens to the society surrounding him and, against all odds, in July 2015 La Buona Scuola was definitively approved by Parliament. Not only was it dictatorially imposed, but it was also based on a political social blackmail: the EU had ordered Italy to give a permanent position to the 300,000 temporary teachers – precari in Italian – who had the legal qualifications to get it; these precari were a minor side effect of Berlusconi’s Riforma Gelmini. Renzi said he would hire them only if the whole Reform was approved. Today, November 2015, only a minor part of the planned 100,000 teachers that had to be hired by August 2015 have been taken into service amid a bureaucratic chaos typical of this latitude (the First Lady got her permanent position a few days ago), revealing the government’s carelessness towards the human beings that are behind the professionals.

La Buona Scuola as homage to the ideology of the scuola/azienda and the making of the teacher/consumer

La Buona Scuola carries on the Berlinguer/Gelmini guidelines. Once again, it is a homage to the ideology of the scuola/azienda. This vision of the school system actually shows an idea of society at large that reminds the fascist scheme of pyramidal control: the Minister of Education appoints a few inspectors who control about 8.000 headmasters who in turn control about 800.000 teachers throughout the country. Many other aspects of La Buona Scuola reinforce the idea of centralization of power and of ‘totalitarian’ control that characterises the Renzi government, as it is made clear by the Constitutional reforms that are under way. As far as the pubblico impiego – the State’s employees – is concerned, its planned reorganization in three mega departments and its trend of giving the administration complete power to decide about resources distribution is another example. Moreover, no destructive aspect of the previous Riforma Gelmini was repealed; on the contrary, it was reinforced through the ‘ideological privatization’ of State school: the possibility the headteacher/manager will have to choose the teachers for his school is an example. He will surely choose those who share the same line of thought, like private schools do.

La Buona Scuola, like most of Renzi’s reforms, follows the the Confindustria’s ideological line, what I have previously defined as ‘Marchionne’s logic’ (Confindustria is the industrialists’ association). The aim to put an end to the contratto nazionale and give extra-money to workers who ‘behave’ is clearly reflected in this reform: in its original draft the scatti di anzianità – the rising of salary as the career proceeds – had to be abolished and substituted by a bonus for teachers evaluated as meritevoli, a trend that will most likely be established in a near future. After one year of negotiations and protests, delays and rethinking, the scatti have remained for the time being but our last nationwide contract goes back to 2008. And the cost for a new contract is surely higher than the ‘charity money’ delivered to praise ‘good teachers’ (200m euros a year); in other words the money for merit is taken from our pockets. Recently, since the Corte Costituzionale has forced the government to sign a new contract for all the State’s employees, Renzi’s cabinet has add a certain amount of money for this purpose to the 2016 legge di stabilità. The average pay rise is going to be 7 euros per worker – minus V.A.T., of course!

The ideology of the scuola-azienda is also further emphasized by the expanded role of the preside-manager who will be like a Far West sheriff who administers justice his own way, with smoking guns in his hands. He will be able to choose part of his teaching staff, and in the most corrupt country in Europe this is surely a guarantee of impartiality. He will choose the ‘good teachers’ eligible for the extra salary, and it is not difficult to foresee they will be the ones who ‘obey’, who are willing to absolve all the collateral ‘school management’ functions the headmaster is giving out and be appointed deputy sheriffs. Besides, since all the headmaster/manager can do is to tolerate the teacher of great didactic and cultural value as a fine ornament, I strongly doubt the teacher who is good at teaching but poor as a bureaucrat will ever be rewarded.

The logic of putting an end to the national contracts and introducing bonuses for the teachers, as the Confindustria’s ideological line imposes, has given birth to the teacher/consumer. Besides the ‘merit bonus’ there is also a 500-euro-a-year one for every teacher who must spend it compulsorily. The teacher/consumer must spend this amount in technology, in tools like books or films or in taking part in compulsory corsi di aggiornamento ( updating courses), a lucrative business allegedly based on the all-Italian bribe system and of depressing cultural content. Now teachers too proudly contribute to the circulation of money and to the rise of consumption goods, one of the basic market principles to make post-crisis economy grow again: put down your books and pick up your… credit card / we’re gonna have a whole lotta fun.

Moreover the private companies which donate money to a single public or private school will get the ‘school bonus’, which means deducing 65% of the amount given from its tax scheme. Which also means financing schools ideologically close to the benefactor. And since the main effort of the new type of headmaster is to look for financers, the ground is fertile for a lasting engagement. The preside/manager will be ‘supervised’ every three years about his students’ success or their abandoning the school; consequently, success, which is already very rarely denied to the student/customer, will be almost guaranteed. Last but not least, the State will continue to give money to private schools: every family with a child attending any type of private school will deduce up to 400 euros a year from his tax money, regardless of its income.

Sit and wait and hope in vain

In conclusion, La Buona Scuola does nothing of what Renzi promised on the day of his inauguration speech:

- re-establish an education system based on culture, knowledge and contents

- a better salary for teachers, similar to the average European nations

- an improvement of their social role and better working conditions

the issues I have been waiting for since the beginning of the new century. I am still sitting here, still waiting for Godot, still trapped in the punitive logic against our profession. And since in 2011 Prime Minister Monti, the outstanding Bocconi professor and rector who had come to save the country after Berlusconi’s disaster, gave me a 10-year extended-time bonus when my service was reaching game over, I think I’ll have plenty of time to sit and wait and hope in vain.